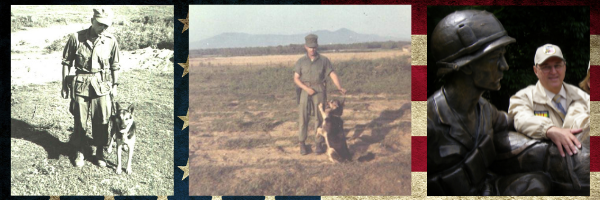

Ron Aiello

By Maria Goodavage

In late 1965, 21-year-old Marine Corporal Ron Aiello figured it was just a matter of time

before he’d end up in Vietnam. The swift flow of U.S. combat forces heading there since

March showed no sign of stopping, and since Aiello was in a Marine Infantry Battalion at

Camp Lejeune, he was sure he was in line for deployment.

So when the Corps asked for volunteers to go to dog-training school and then be

assigned to a “restricted area,” Aiello stepped forward.

“I thought if I have to go to Vietnam, what better way to go than with a dog at my side,”

says Aiello.

A few months later, he and his German shepherd scout dog, Stormy 476M, touched

down at Da Nang Airbase in one of two C-130s transporting members of the 1 st Marine

Scout Dog Platoon. After 20 days of transitioning the dogs from the jarring change of

winter at dog school in Fort Benning, Georgia, to the warm, muggy climate there, they

were ready to be deployed on missions.

Aiello had no idea that this first operation would be a life-or-death proving ground for

their months of training.

He and Stormy were assigned to lead a platoon of Marines in a search of two villages

where some locals were suspect of helping the Viet Cong. They walked house to house

in the first village, which was made up of structures cobbled together with a

hodgepodge of bamboo, straw, and scrap metal.

Aiello and Stormy would enter a house first. Stormy smelled and listened for danger.

She could root all kinds of trouble, from someone hiding in an underground bunker to

weapons concealed in walls. Once Stormy was done with her inspection, other Marines

entered to do a physical search without worrying about setting off a booby trap or

explosive.

With one village cleared, Aiello and Stormy led the Marines on a heavily traveled dirt

path to the next village. Along the way, the pair came to a small clearing, about 50 by 70

yards. They walked in to check it out. After a couple of steps, Stormy came to an abrupt

stop. Her body tensed, tail high, her attention riveted to something in a tree to the right.

This was her alert.

Aiello automatically went to take a knee. But before his knee hit the ground, he heard a

gunshot. He could sense a bullet whizzing over him and in that moment, he realized that

if he’d still been standing, it would have hit him in the head.

He knew he had to take instant action or his first deployment with Stormy could be his

last. He saw a mound of dirt about ten yards to this left and yelled for his leashed

partner to stay with him. They bolted to it and jumped over to the other side for

protection. An infantryman behind them kept them covered and fired up to the tree

where Stormy had been looking. He took out the sniper, and they moved on.//

If Aiello hadn’t listened to Stormy, he might not have made it through his tour in

Vietnam. And working dogs and their handlers decades later would have missed out on

incomparable support – the kind of support Aiello and other dog handlers in Vietnam

never had.

In the year 2000, Aiello co-founded the United States War Dogs Association (USWDA),

a nonprofit organization that supports current and past military working dogs and

handlers. USWDA has several essential missions, including promoting the history of

military working dogs, establishing war dog memorials, and educating the public about

military working dog teams.

But the programs that make the organization especially beloved in the working-dog

world are the ones that directly benefit dogs and handlers. In the last 18 years USWDA

has been responsible for sending 25,000 care packages to deployed dog teams. Dogs

typically get essential items like Doggles/Rex Specs, dog boots, cooling vests, K9

blankets, ear and eye wash, paw protector cream, and shampoo, as well as goodies like

dog treats, travel water bowls, and loads of hardy dog toys, like Kongs. Handlers

receive coveted items like favorite snacks, books, and toiletries.

Another prized program began more recently. In 2014, Aiello received a call from a

woman who had adopted a military working dog with her family. They were desperate

for help. The prescription meds their dog suddenly needed were expensive, and the

woman was at a point where she had to choose between putting food on the table or

getting her dog these essential medicines.

Aiello didn’t think it was right that the military leaves medical expenses in the hands of

those who adopt the dogs. The next day he came up with a program that would provide

free prescription medicines to retired military working dogs. More than 1,000 dogs are

currently enrolled in the program, which recently opened to include retired dogs from the

Department of Homeland Security. The assistance can be lifesaving for the dogs, and it

eases the financial burden for their devoted adopters.

Aiello has dedicated most of his time in the last 21 years to the causes supported by

USWDA. But a couple of years ago he started thinking about passing the torch to the

next generation of handlers. He wanted to help transition the organization to new,

younger leadership while he had the time and energy to do so. He handpicked the next

president, with his board’s full support. Earlier this year, Chris Willingham, a respected

and well-liked leader in the military working dog world, became president of the

organization.

“Ron has been a friend and mentor of mine for years and I've been on the receiving end

of support from the USWDA for over 15 years,” says Willingham, who retired from the

Marines after a long and storied military working dog career. “So when Ron asked me to

take over it was incredibly humbling and a huge honor.”

Aiello says he’s thrilled to have helped create such a legacy – not only because of all

the handlers and dogs he’s helped, but because of Stormy.

“The United States War Dogs Association was and still is a living memorial to Stormy –

and the other military dogs that served in Vietnam,” he says.

Like the majority of dog handlers from that war, Aiello doesn’t know what became of his

four-legged partner and best friend. Some thirty-eight hundred dogs deployed there and

are credited with saving many thousands of lives while protecting troops, leading jungle

patrols, and detecting ambushes and mines. But the military deemed some of the dogs

too dangerous to return home. Indeed, many of the sentry dogs had been trained to be

so vicious that even their handlers had a hard time controlling them.

But sentry dogs were just one type of dog in the war. There were others, including

scouts like Stormy, and trackers. Still, only about 200 dogs would ever return home.

Besides the behavioral issues, there was concern that even the non-aggressive dogs

would carry disease from Southeast Asia—something that could have been

circumvented by a quarantine once they were home.

The majority of dogs were left behind or euthanized.

Many handlers from Vietnam still can’t talk about their dogs without their eyes going

distant, their throats catching. The lucky ones hold onto a memento of their former K9 –

usually a collar or leash. Most just have the memories, underscored by the pain of

knowing, or imagining, the fate of their wartime best friend.

Aiello says leaving Vietnam was the hardest part of his deployment. He and a half-

dozen other Marine dog handlers had tried to extend their time there in order to do

another tour with their dogs. But their requests were turned down.

He wasn’t sure how much longer he’d have with Stormy. One day the handlers got the

news that their replacements would be coming – and that they’d be there to take over

their dogs the very next day. That night, most of the handlers slept in the kennels next

to their dogs before having to say goodbye.

Aiello was grateful he was able to meet Stormy’s new handler. He sat down with him for

a couple of hours, and tried to tell him everything about Stormy, from her likes and

dislikes to the different ways she would give alerts on patrols.

“I then shook his hand and said good luck, and take good care of Stormy. She’ll save

you when needed,” he says.

He grabbed his sea bag and didn’t look back. He and the other handlers were instructed

not to go back to Camp Kaiser, their base camp, to try to see their dogs while they were

still in country, because the new handlers needed to bond with them. He left Vietnam

and never saw Stormy again.

In the years that followed, Aiello thought about Stormy every day. When he heard the

scout dog platoon was pulling out of Vietnam, he was hopeful there was a chance

Stormy was still alive. He wanted to adopt her. He wrote to Marine Corps headquarters

twice, with registered letters, but he never got a response.

The best fate he can imagine for her – what he hopes happened once he knew she

didn’t come home – is something most handlers today would find devastating.

“I would like to think she was KIA in Vietnam,” he says.

If Stormy was killed in action, he reasons, she could have worked with a loyal and loving

handler and not known what hit her. The other options are too awful. He can’t go there

anymore.

He prefers to remember the days when the two of them were fighting the good fight in

the jungles and rice paddies together. Their missions ran anywhere from one day to

three weeks. Together he and Stormy rooted out countless weapons and booby traps,

as well as Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers in hiding.

Aiello credits Stormy with saving hundreds of lives of Marines and civilians. Her finds

didn’t always lead to dramatic scenarios. Some of the most important ones were fairly

subdued affairs. Like the time they were between houses on a search and Stormy

stopped and alerted. As always, Aiello took a knee, as did his Marine bodyguard.

“The only thing there was some tall grass, so we went in closer, but Stormy stopped

before we got to the grass and just looked straight down to the ground, so we were

thinking explosives, some form of a booby trap,” Aiello recounts nearly 55 years after

the mission. “So my bodyguard takes out his knife and starts to dig. About six inches

down, then 12, then 18.

“He shoves his arm down into the hole and comes out with a plastic bag in his hands. In

the bag were papers. We took them out and looked at them. Of course, we couldn’t

read what was on them. So we turned them in to command,” he says.

As always, Aiello rewarded Stormy on the spot with lots of hugs and praise. “That’s

what she loved and of course I loved it, too,” he says.

The next day Stormy got bonus hugs when Aiello learned the papers contained tactical

plans of the North Vietnam soldiers.

Of all their adventures together, though, one of the most rewarding had little to do with

war. It had to do with connecting in unexpected ways with strangers.

It happened during monsoon season. The rain poured down day and night. He and

Stormy were leading a company-sized operation. Everything was mud. Nothing was

comfortable.

“It was getting late in the day one day and we were going to set up a base camp for the

night. I would usually try to sleep with Stormy in the center of a village in a clearing.

Stormy would sleep by my side so I felt quite safe.

“This time there was nothing but mud, so I spotted an old bed box spring – and I mean

spring just rusted out. So I dragged it over to the center of the village and laid my

poncho on it. This is where we would sleep for the night.

“Out of the corner of my eye I spotted one of the villagers motioning to me. He kept

pointing to me and Stormy and putting his hand to his mouth. I finally figured out what

he was saying. He was inviting me and Stormy to eat with them.

“We walked over to their house, which was not really what we think of as a house. It

was made of bamboo, straw, tin metal. Two, three rooms all open, dirt floors, mats for

beds. Under an outdoor roofed area there was an old wooden table surrounded by a

few old wooden chairs. The man motioned for me to sit down. Stormy lay down at my

right side.

“They had a little boy about three years old who sat across from me. The man’s wife

was cooking and held their baby, who was about three or four months old. She and her

husband put the food on the table and then sat down to dinner.

“I remember so well all of us sitting around the table. It was a tight fit. The meal

consisted of stir-fried vegetables, no meat. It was delicious. All I could do was smile and

nod my head since we could really speak to each other where we would understand.

When were done, I thanked them and then came back and gave them my C-rations.

“To this day I still remember them and pray to God that they survived the war and had a

good life.”

He’d like to think the same about Stormy. But he knows better.

So even though he’s officially retired as USWDA president, he’s still devoting himself to

the organization as it transitions to its next stage. He’ll continue to be involved, though

to a lesser extent, in the future, in part because he’s passionate about the group’s

missions. But beyond that, he wants to continue to work at least a little on behalf of the

dog he still misses to pieces some days.

“I was, and always will be, very proud of Stormy,” he says. “I hope I’ve done her

proud.”

Maria Goodavage is the New York Times bestselling author of four books about working

dogs: Soldier Dogs, Top Dog, Secret Service Dogs, and Doctor Dogs.

www.mariagoodavage.com

FB: @soldierdogs, @doctordogsnews