VIETNAM WAR

Vietnam

Introduction of Dogs

The French gave up Vietnam as a colonial stronghold after the fall of Dien Bien Phu on, May 7, 1954. Later that year the Geneva Accords divided Vietnam along the 17th parallel; the north communist, led by Ho Chi Minh and to the south a quasi-democracy led by emperor Bao Dai. Within a few years the United States felt compelled to get involved with men, material, and military working dogs (MWDs).

The U.S. Air Force began an experimental program in 1960 at an old French dog compound at Go Vap on the outskirts of Saigon. It was mostly a rehash of what was already learned during WWII. A year later the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAGV) took over and looked to establish a dog program for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). The recommendation was to provide 468 sentry and 538 scout dogs to the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). It was believed that 300 dogs, to be purchased in West Germany, would be sufficient to launch the program. Advisory veterinarians were also deployed because RVN did not have a single doctor familiar with dogs. Four instructors were also dispatched, including SFC. Jesse Mendez to train ARVN soldiers the basic skills of a scout dog handler. The air force provided four instructors and ten sentry dog dogs to help establish better airbase security.

By 1964 the ARVN had 327 dogs in inventory but the attrition rate due to disease and accidents would hamper the RVN dog program right up to the fall of Saigon in 1975. Many issues constantly plagued the MWD program as ARVN handlers were often reluctant to praise their dogs for a job well done and to feed them properly. It was simply a cultural difference between how Americans respected and treated their dogs compared to the indifference of many Vietnamese handlers. The Americans would fare far better with their MWDs as the war effort ramped up.

Caption: American advisors often accompanied ARFN scout dog handlers out in the field. This was crucial to determine how well the scout dog teams were working. (NARA)

Caption: Few South Vietnamese veterinarians were qualified to care for MWDs. Most medical care during the war came from American medical personnel. (Carlisle Barracks).

American Dogs Arrive

The United States would not deploy MWDs to Vietnam until a successful VC sapper attack took place on July 1, 1965 at Da Nang airbase. Project Top Dog was launched, sending over 40 sentry dogs and handlers. This was followed by Project Limelight, which escalated the number of dogs and handlers to cover every airbase in Vietnam. The Air Force sentry dog force peaked in January, 1967 with 467 sentry dogs and then declined thereafter. One reason was that the airbases were becoming so noisy and congested that the dogs could not work effectively.

Caption: A2C Richard Morley (35th SPS) with Satan at the perimeter at Phan Rang Air Base. Sentry dogs proved to be both a physical and psychological deterrent for the enemy. (NARA)

The army quickly followed suit and began deploying sentry dogs in 1965. The inventory of dogs would peak in 1970 with about 300 teams spread out across Vietnam. Beginning in 1966, the Marines and Navy each kept a sentry dog unit at Da Nang airbase and nearby Marble Mountain. Most of the handlers and dogs for the Army and Marines were trained at the U.S. Army Pacific Sentry Dog School in Okinawa. Other handlers received their training at Fort Gordon, Georgia and then obtained their dogs and an additional eight weeks of training at Lackland AFB. To fill the expanding need, men were yanked from various security positions throughout Vietnam and given on-the-job-training (OJT).

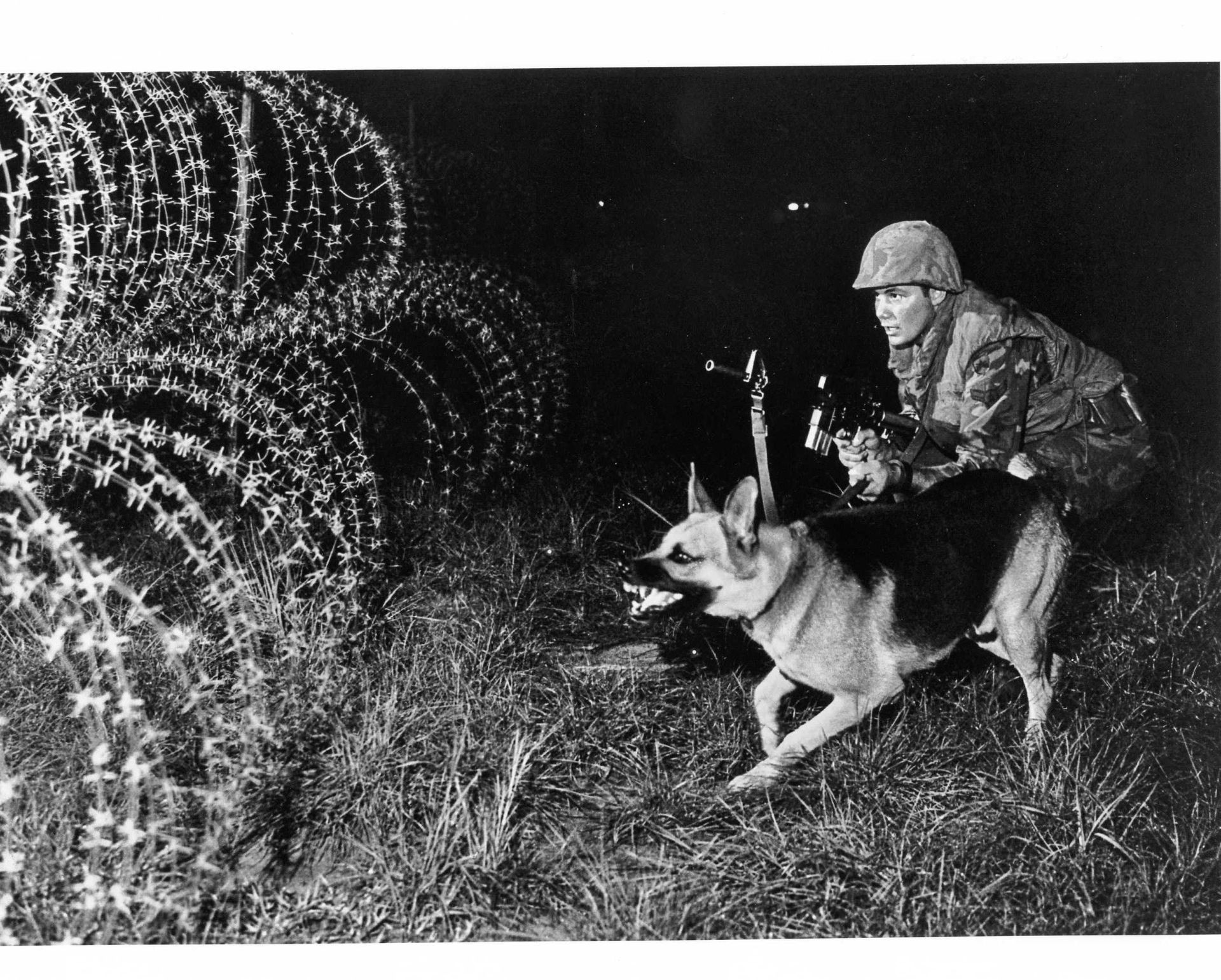

In just a few months, sentry dog teams proved their worth as Vietcong sappers began causing problems at various air bases. With a succession of failed attempts, the VC attempted to disguise their human odor by using a variety of sprays, including pepper and a garlic-like herb called toi, all to no avail. Probably for this reason, on April 13, 1966, the VC directed ten mortar rounds at the Tan Son Nhut kennels.

The largest encounter during the war involving sentry dog teams and the VC took place at the same airbase on the night of December 4, 1966. The encounter left one handler and three dogs dead and an untold number of VC killed. It began shortly after midnight when A2C Leroy E. Marsh and his dog Rebel detected about seventy-five VC sappers. Marsh released Rebel who was quickly cut down by automatic fire, but allowed his handler to radio for a reaction force. About an hour later, A2C Larry G. Laudner’s dog, Cubby, alerted to the same group. Laudner released Cubby who was shot and killed. As dawn approached A2C Dale Sidwell and his dog Toby alerted to the group. Sidell returned fire and Toby was shot and killed. Handler George Bevich was then shot and killed while trying to rescue a wounded officer. With daylight, the VC went to ground and hid waiting for nightfall to emerge and an attempt an escape.

That evening, A2C Robert Thorneburg and Nemo (A534) approached an old cemetery on base. Nemo alerted and Thorneburg released the dog. Nemo killed one VC before being shot in the face as his handler returned fire and was also wounded. When the reaction force arrived they found Nemo protectively covering Thorneburg’s body.

The bullet had entered Nemo’s eye and exited his mouth taking part of his nose. Base veterinarian Captain Raymond T. Huston wasn’t sure they could save him and might need to put him down. Incredibly the medical staff performed a tracheotomy, several skin grafts and removed his right eye. Although the Air Force tried to put him back on patrol, the 95-pound warrior never fully recovered. On 23 June 1967, Nemo returned to Lackland AFB and lived out his life as a K-9 recruiter. In poor health, he was euthanized 18 December 1972 and returned to Lackland for internment.

Caption: A2C Robert Thorneburg (in hospital pajamas) and A3C Leonard Bryant visit with Nemo shortly after the VC attack at Tan Son Nhut. Bryant was Nemo’s first handler when the pair arrived in Vietnam. (NARA)

The last battle death of an Air Force canine sentry took place on January 29, 1969. The majority of sentry dog deaths during the war can be attributed to spoiled food, heat induced illness, and snakebites.

The military would shift from vicious sentry dogs that poised a risk to handlers, veterinarian technicians, and kennel maintenance personnel to a trained dog that that could achieve a multipurpose role such as crowd control, tracking, and escort service. In 1968, a program began to recruit and train “patrol” dogs with the assistance of the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department. This program would evolve and develop what we commonly see today; the police K-9. A dog that could attack on command but handle a number of tasks while friendly around people.

Return of the Scout Dogs

In 1965 President, Lyndon Johnson cemented the American involvement in South Vietnam by committing 183,000 troops to the fight. This also included introducing scout dogs although only the 26th Infantry Platoon Scout Dog (IPSD) remained, a relic from World War II. Expansion began in September of 1965 and the Department of Defense (DoD) established an annual quota of 1,000 dogs. This would be tough to fill as the military competed with police and civilian security outfits also seeking canines for their use. In December the DoD wanted to establish 13 Army scout dog platoons and three Marine units.

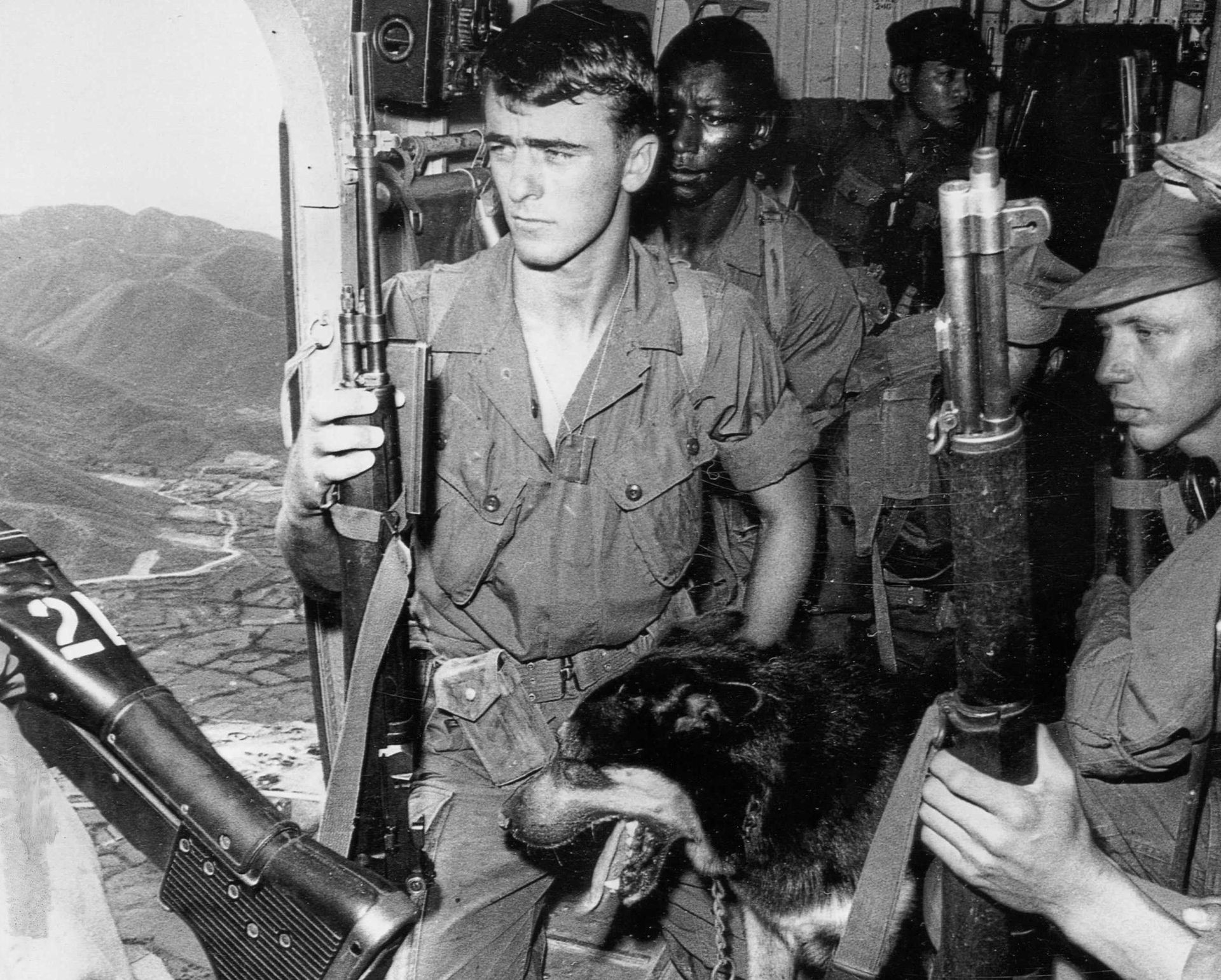

A startup shortage also existed between handlers and instructors for the 12-week scout dog course. Only 40 per cent of the instructors had experience in Vietnam. All handlers in the program were to be either “volunteers or selected individuals.” This was desirable since motivation in handlers could only be achieved if they truly liked dogs. The Marines started first and fielded two platoons that deployed in February 1966. It was the first time since World War II that Marines employed dogs in combat, with the Doberman pinscher put aside in favor of German shepherds. The army followed with the 25th IPSD in June 1966. Early success proved once again the effectiveness of scout dogs on the modern battlefield.

Caption: Besides helicopters M-113 armored personnel carriers (APC) were used for transport. The APC carried 11 personnel and one driver. And in this case one dog. (NARA)

Caption: Handlers from the 49th IPSD take a break with their dogs during Operation Fairfax in 1967 (NARA)

To support the teams sent out to the field, Bien Hoa, located a few miles from Saigon, became home to the USARV War Dog Training Detachment and was set up as the nerve center for the deployment and training of all scout dog teams in Vietnam. Their motto “Forever Forward” was appropriate since scout dog teams typically led the patrols, commonly referred to as, “walking point.” Army scout dog teams peaked on January 20, 1969 at 22 platoons with the arrival of the 37th IPSD. The Marines retained four platoons.

On their arrival in Vietnam, all scout dogs were worked on a 15-foot leash. This had its good and bad points; the handler could easily control the dog with a minimum of hand and voice signals while on patrol. It also meant he would be in close proximity if his dog should trip a booby trap. The Army started to train off-leash scout dogs in 1968 and deploy them the following year. The advantage was safety and the use of both hands. This was nothing new as it was already accomplished during World War II in the Pacific.

Handlers always put great stock in their dog’s capabilities. Their lives depended on it. But a wise one always tempered that judgment. “One eye was on my dog and the other on the terrain around me, because I didn’t trust the dog completely,” said Sgt. Robert Kollar, 58th IPSD. Kollar worked Rebel (M421) beginning in September 1968. “As far as I was concerned,” Kollar stated, “he [the dog] had the mind of a four-year old. If a human can screw up, and enough of them did, I sure as hell know a dog can.”

Caption: Robert Kollar with Rebel (M421). Notice he is sporting the M-16 rifle while many handlers were issued the shorter-barreled CAR-15 later in the war. (Lemish collection)

Mine and Tunnel Dogs

Technology advanced tremendously in the detection of explosive mines since World War II. Yet the VC and NVA possessed little technical prowess and the U.S. military quickly realized that the cruder the device, the more difficult it is to detect. The U.S. Army Limited Warfare Laboratory (USALWL) was tasked in 1968 to develop training for dogs to detect mines and booby traps. Since they had no experience in this field they contracted to a civilian company, Behavior Systems, Inc. located in Apex, North Carolina.

The company trained 14 dogs to detect mines and booby traps and another 14 to locate tunnels only. The final test took place at Fort Gordon, Georgia, on July 18, 1968. The military was not enamored by the civilian trainers and one captain purportedly referred to them as “longhaired freaks.” The dogs worked flawlessly, detecting mines, booby traps, hidden personnel, and tunnels.”

A colonel from Fort Gordon was not impressed and believed improper camouflage gave visual clues. When a German shepherd alerted to a punji pit, the colonel believed it was a false alert and went forward to inspect the site. After declaring it a false alert, he stepped around the dog and fell in. Fortunately no punji stakes were in place. The USALWL decided to accelerate the training program.

This led to establishing the 60th Infantry Platoon at Fort Gordon in August 1968, arriving in Vietnam in April, 1969. Usually, the handler followed 15-50 yards to the rear, depending on the action. During the first three months in-country, the dogs alerted to 76 trip wires, 21 tunnels and punji pits, and alerted to enemy personnel on numerous occasions.

Too often, the dogs were overworked. In one case a mine dog covered 21 miles of hard surface in just seven hours. The dog, bordering on heatstroke, suffered painful blisters and cuts to all pads on his paws. At the end of the three-month trial period, 85 percent of the patrol leaders believed they enhanced security. Additional teams would be deployed to support both Army and Marine units as the war continued.

Caption: A tunnel dog locates a VC spider hole in Vinh Long. The dog’s responsibility ended there. It is a myth that dogs entered the tunnels to challenge the VC. That dangerous job was given to volunteers, armed with a Colt 1911 pistol, known as “tunnel rats.” (NARA)

Tracking the Enemy

The United States military often had a difficult time engaging the enemy. The Viet Cong, after conducting a mortar attack or ambush, often disappeared into the dense jungle without a trace. An early example is a mortar attack on Bien Hoa Air Base in October 1964. Six B-57 bombers were destroyed and another 20 aircraft severely damaged. Although search parties went out immediately after the raid, not a single VC soldier (and it is estimated that 300 participated) could be found.

The Army had no experience in tracking men over terrain. That skill disappeared from their ranks over 100 years earlier. The military turned to the British who had vast experience tracking insurgents is such diverse locations as Kenya, Cyprus, Malaya, and Borneo. Trouble was, Great Britain remained neutral during the Vietnam conflict as was Malaya, where the Jungle Warfare School was located. Diplomatic arm twisting and keeping everything secret, an agreement was reached in 1966 to train 14 tracker teams. Training began in Malaya, but was eventually moved to Fort Gordon, Georgia.

Black or yellow Labrador retrievers were favored as tracker dogs as they were docile and could tolerate the heat reasonably well. The big advantage they held over their German Shepherd brothers, is that the favored the dead scent of ground sniffing, while most shepherds air-scented. Training for the dogs was typically eight months. Although not trained to locate booby traps, many often did. The main mission for a tracker team was to reestablish contact with a fleeing enemy, but not engage. Also supporting the mission was a man trained for “visual tracking” to read the clues on the trail that the enemy left behind.

Caption: Tracker dogs were always kept on leash in the field. The fresher the track the better, but some dogs could follow one 24 hours old. (NARA)

Four-Footed Radar

More than 3,800 military working dogs contributed to the war effort in Vietnam and it has been determined they prevented upwards of 10,000 casualties (although this has frequently been erroneously reported as “lives saved.”) Army scout dog teams alone conducted more than 80,000 missions. Due to poor recording keeping, it is not known the complete activity of Army tracker, mine/tunnel dogs, and Marine operations. Air Force sentry dog teams worked thousands of hours on nightly patrols. Their effectiveness is not measured by the number of encounters with the enemy but how their presence dissuaded sapper attack on airbases.

Caption: Marine Sgt. Tim Hiller and his scout dog Rip take a short break on a sweep ten miles south of Da Nang (NARA)

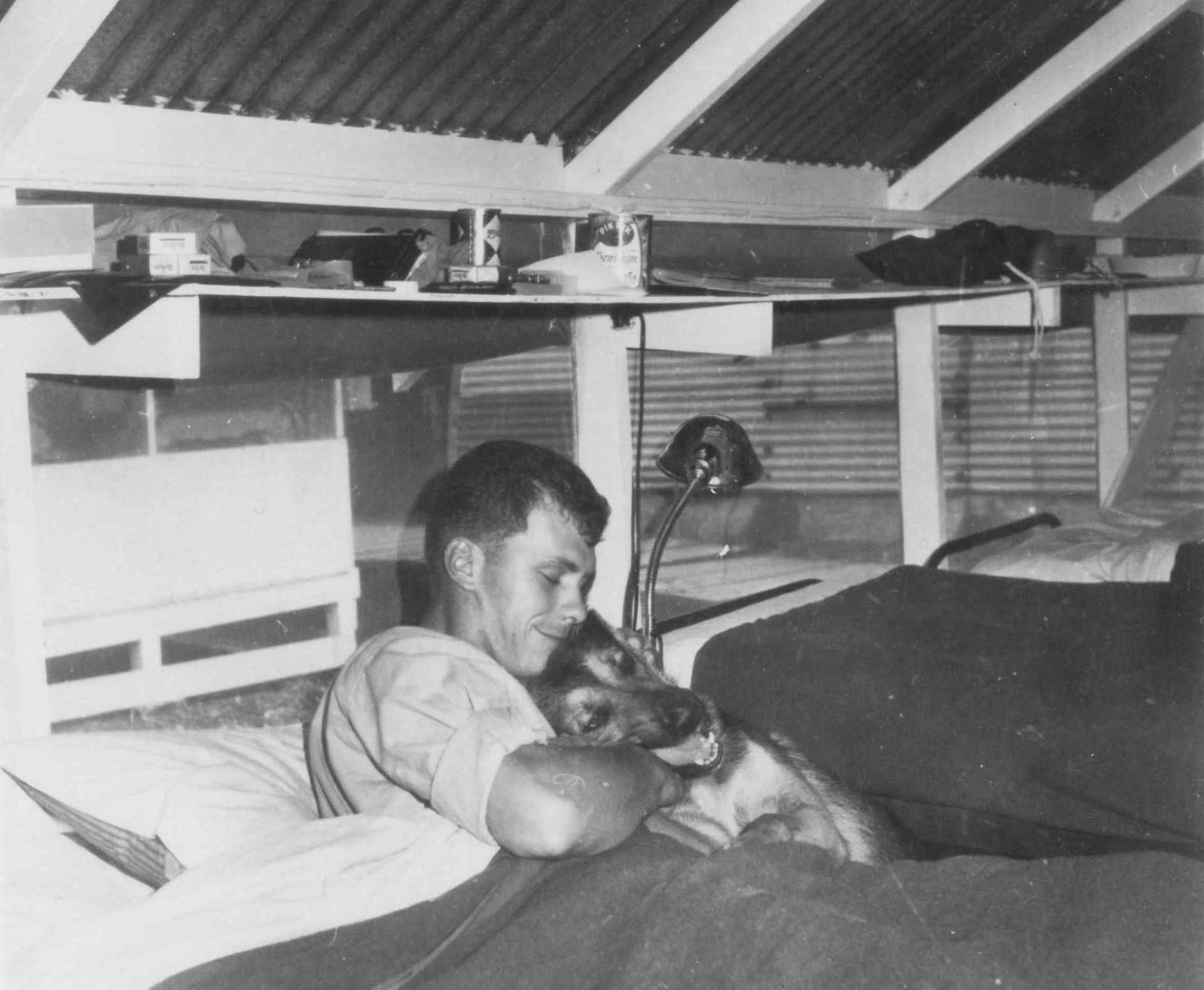

It is always a team effort, handler and dog. And the first patrol has got to be the scariest, although it can often turn out well as, was the case of Brian Taras (39th IPSD) and scout dog Gretel (X399). In August 1969, working in the Central Highlands on their first patrol, Gretel alerted to a claymore mine a good 90 meters off-trail. Later that day, the pair found a tunnel and rice cache on a village search. A couple of months later, the team found a battalion-size VC headquarters chock full of ammunition and documents.

Even the best dogs were not infallible. The wind could blow in the wrong direction, or – because of the heat and humidity – the handler and dog were just spent. Perhaps the handler missed the dog’s alert. A truly viable asset, dogs aren’t machines and the military needed to understand that. All told, 263 handlers were KIA in Vietnam – as were approximately 350 dogs. By far the number of canines killed was not by the enemy but for medical reasons such as tropical diseases, poor diet, or heat exhaustion. Less than seven percent of the dogs were wounded-in-action (WIA). Many dogs were wounded more than once. For instance army scout dog Mitzi (X007) was WIA five times!

Caption: Scout dog Lux as an eye wound administered to by personnel from the 936th Veterinary Detachment. Given the conditions in Vietnam most dogs received excellent veterinary care. (NARA)

Many people may find the use of military dogs insignificant or even trite compared to the thousands of men killed and wounded, huge battles, massive airpower, and continuous aerial bombardment that occurred during the 10,000-day war. For the dog handlers – whether they came home or not – was often determined by their canine partner. It didn’t matter if you were on a patrol in the jungle or sentry duty at night. Military working dogs had an immediate impact on those around them. Like Korea, the military determined that dogs reduced casualties by at least 65 percent. The VC didn’t consider them insignificant either and offered a “bounty” if a dog or handler was killed.

Caption: Marine Corporal Isaiah Martin comforts his dog shortly after being hit by a NVA sniper round. (NARA)

Aftermath

President Richard Nixon formally declared the withdrawal of troops and the “Vietnamization” of the war on September 16, 1969. It would still take several years and many more dead and wounded to accomplish this task. There was still a lot of fighting yet to be done. Dog teams continued to be shipped overseas as late as 1970.

During World War II, it was expected that the dogs would be returning home when the war ended. Richard Zika, a handler with the first dog unit in Burma, knew that as fact. “It was expected when we returned home the dogs would be going with us. If anything else happened, well, let’s just say they would have been a mutiny.”

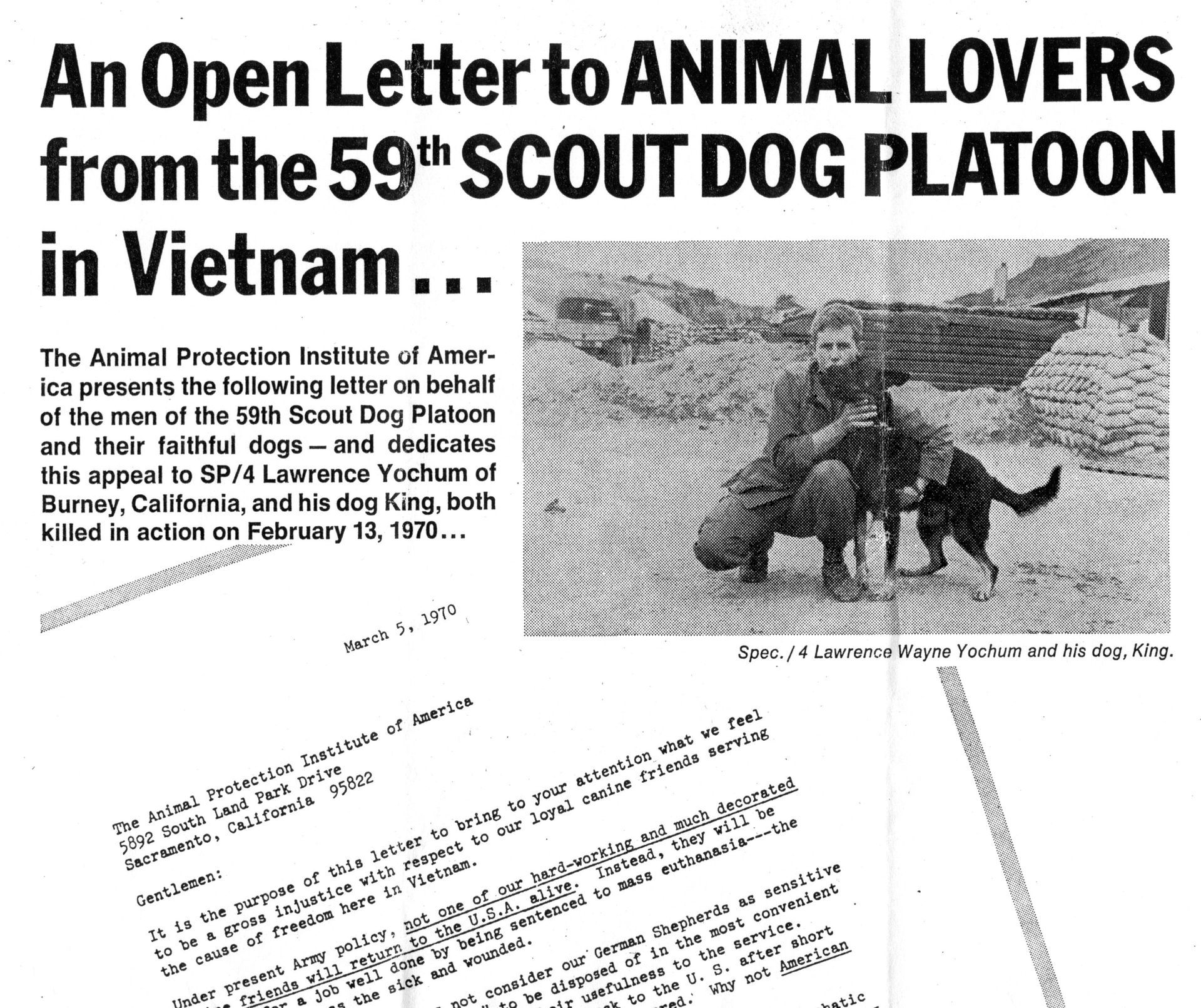

Vietnam would be entirely different. Military dogs are now considered equipment, the same as a rifle or a tent and the property of the United States government. The military would publish a number of reasons on why the dogs had to be left behind. The biggest red herring they used is the canines may have acquired communicable diseases that could be transmitted to the homeland dog population. Another is that the dogs could not be “detrained” and poised a potential threat to the civilian population. In the words of USMC Major General C.B. Drake, “To place such an animal in a civilian community would be most hazardous and could ultimately lead to serious injury or death.”

None of the excuses advanced by the military held any water. The real reason (never stated publicly) is that it would be cheaper and less labor intensive to simply leave the dogs behind.

Everyone wanted to get out of Vietnam. In an era before the internet, protests opposing this “no dog return policy” took the form of letter writing campaigns, calls to elected officials, and letters to newspaper editors. A couple of bills were floated in Congress but they died quietly in committee. Those involved included dog handlers, animal rights organization, and a number of concerned citizens. At the time most Americans did not even know there were military dogs in Vietnam and how many were employed.

Caption: The Animal Protection Institute of California printed posters of the plight of war dogs in Vietnam, attempting to raise funds for their return. (Lemish collection)

At one point mass euthanasia was considered but quickly dismissed. That would not fly with anyone back home if word got out. To quell the growing discontent the military adopted an appeasement policy; “medically fit” dogs would be reassigned to other locations or returned to the United States. Eventually about 285 dogs were able to board a “freedom bird” and leave Vietnam. Under no circumstances were civilians able to adopt the K-9 veterans. The remaining dogs would be turned over to the ARVN or euthanized for medical reasons. Either way, it was an inglorious end to an illustrious saga forged by all military working dog teams.

As with many men and women who served in Vietnam, it would take decades before military working dogs were recognized for their contribution to the war effort. That is why they are often referred to as “America’s Forgotten Heroes.” But recognition would eventually come as the public learned of the contribution from our four-legged friends. The lessons learned from Vietnam would be carried forward to this very day. This would manifest in training, capability, retirement policy, education and recognition.. Technology advances at lightning speed but the dog remains.

Caption: The Animal Protection Institute of California printed posters of the plight of war dogs in Vietnam, attempting to raise funds for their return. (Lemish collection)

Caption: Imprints of a military dog team. Not just in the soil of Vietnam but in the hearts and minds of those that served. (Courtesy Gary Zemel).