KOREAN WAR

KOREA

1950- 1953

After WWII, the Army gutted the military dog program and only the 26th ISDP (Infantry Scout Dog Platoon) remained active. Their mission at that time was to show the American public the capabilities of the military working dog in demonstrations around the country. The War Department had intended that the scout dog platoons be continued in the post-war establishment. During a conference held at Fort Benning during June 1946, the Army’s Committee on Organization met to debate the situation. Committee chairman Brig. Gen. Fredrick McCabe discussed the contributions dogs made during the war and recommended that “Infantry War Dog Platoons be retained and be attached to infantry training units.” As is often the case within the military, a good recommendation will fall on deaf ears.

In 1946 the Quartermaster Corps discontinued its program of acquiring dogs loaned from U.S, citizens and began purchasing them directly from breeders. As a consequence, Dogs for Defense dissolved. In May 1954, a new directive changed the responsibility of dog training. The Quartermaster Corps would still procure dogs, but training shifted to Army Field Forces at Fort Monroe, Virginia. The Quartermaster Corps - in a quandary at this time, would often issue confusing and contradictory statements at this time, such as:

- It was discontinuing the K-9 Corps.

- It no longer accepts donations.

- It still accepts donations.

- Dogs would be purchased only from breeders.

- The Army would begin its own breeding program.

Before hostilities began in Korea, the Army maintained about a hundred sentry dogs, mostly around Seoul. Most of these dogs were killed or starved to death as North Korea launched a major attack against South Korea on June 30, 1950. Within days, the United Nations agreed to bolster the defences of the faltering South Korean forces. A month later, the first Americans entered the conflict.

The 26th ISDP landed in Korea in July 1950, piecemeal, with just seven handlers and dogs. Others were soon to follow. Their missions were simple yet dangerous: having the scout dog provide a silent alert of the enemy during patrols, observation posts, and outposts forward of the allied battle position. Their effectiveness was well documented. In a review of after-action reports, patrols led by scout dog teams were credited with reducing causality rates by 65%.

Caption: Joe "Heavy" Thompson returns from a patrol with his scout dog. Note the M2 carbine and MK2 grenades. Photo: Robert Fickbohm

Below is a short narrative of a reconnaissance patrol that involves several characters. The date is May 16, 1952. Nighttime. The place is somewhere in Korea. Leading the American squad of 16 men is Lt. Peter Jourdonnias. Opposing them, somewhere out in the darkness, are an unknown number of Chinese soldiers. Both participants are drawn together in a brutal war that will bring these combatants together - or perhaps not. For the Americans have a weapon the Chinese do not possess – a scout dog named Arlo. And alongside this so-called weapon is his handler, Sgt. Jack North. Each side will be separated by just a few hundred yards in a deadly cat and mouse game between two opposing forces. Ultimately, what takes place during this encounter will not be decided by the men involved, but with a six year-old German shepherd dog, that has just one purpose in mind - one that he was trained to do – to protect the men that follow him.

The plan was simple: the American infantrymen would leave their post at the MLR (main line of resistance) during the night and reconnoitre a road which might be used as a tank route north toward enemy held territory. The patrol is to check three bridges to see if they could support tanks. Jourdonnias was instructed not to engage the enemy unless absolutely necessary. The men carried two BARs, and 16 M2 carbines. Each man carried 400 rounds of 30-caliber ammunition and two fragmentation grenades.

The patrol did not have Sgt. North or Arlo on the point when they first started out as the wind was on their backs. For the scout dog team to be effective they needed the wind on their nose. After scouting the three bridges, North and Arlo were placed on the point. In his own words, North later related in an after-action interview report:

“After walking about twenty five yards Arlo gave me a very strong scent alert. I signaled for the group to drop to the ground and motioned for Lt. Jourdonnias to come forward. I told him that Arlo had given a very strong scent alert and that someone was immediately ahead but did not know how far. He [Jourdonnias] deployed fourteen men on the right side of the road and two on the left. I remained on the road with Arlo.

Lt. Jourdonnias stated that the patrol was to remain in position until daylight. After about 30 minutes, Arlo, his ears pointed straight up, appeared to sense some movement to his left. His head seem to move as if he detected some noises. No one in the patrol was able to hear a sound. About fifteen minutes later, a noise rang out to the left [in] front of us. Voices could then be heard.

"At this point Lt. Jourdonnais decided to move up the road to see if the enemy could be detected. We moved about a 100 yards without further alert from the dog. The group returned to the MLR without incident, arriving about 0100. It is the alertness of the dog that saved the reconnaissance patrol from certain ambush.”

Did Arlo save the platoon? It is really not known what would have happened to the patrol had there not been a scout dog along. One aspect of using dogs in warfare is just how many lives may have been saved by not engaging the enemy when an early silent alert is given of their position. There is no true way to measure that. For North and for that matter Arlo, the results speak for themselves – everyone came back in one piece.

This was just one patrol, which went without incident during one night, by handlers of 26th Infantry Scout Dog Platoon (ISDP). But it would be played out time and time again. The only scout dog team involved during the Korean War was the 26th ISDP. Yet this platoon made more than 1500 combat patrols during the course of the war and just about everyone was conducted at night.

The 26th IPSD and the 2nd Aviation Company devised a way to quickly transport scout dogs using a Bell H-13 helicopter. Photo: NARA

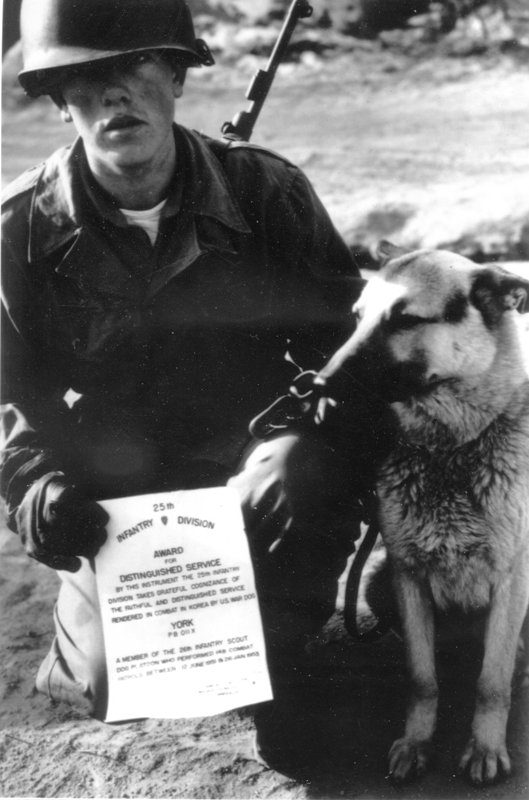

One scout dog in particular was noted for his service. An eight year-old German shepherd named York (011X) was presented an “Award for Distinguished Service.” York led 148 combat patrols and never lost a man. He eventually returned to Fort Benning and was interred with honors at the age of twelve.

James Partain and York after receiving the distinguished service citation. Photo: NARA

As good as they were, patrols led by scout teams suffered. Scout dog Champ was on his 39th patrol when he stepped on a mine. Champ was killed instantly and his handler wounded severely. Scout dogs operating in Korea were not trained to alert to mines or booby-traps.

Champ was brought back to based camp for a proper burial service. Photo: Robert Fickbohm

So how does one account for the actions of scout dog Happy?

While on a nighttime patrol and working point, handler Alvin Steenick noticed his scout dog Happy stop in his tracks and freeze. It was not the type of alert that Steenick had seen before. He pushed the dog ahead but Happy refused to move.

Steenick told the platoon leader that there was an unknown danger ahead. With the platoon leader pissed that there was no forward progress, he stepped ahead of the stalled war dog. And a second later there was an immediate explosion. It was a grenade booby trap. The platoon leader and Happy were killed instantly. Steenick received serious injuries.

This action and the serious consequences that followed would be repeated again many times - not just in Korea but in Vietnam. Although not trained to detect booby traps, Happy had sensed something amiss. The handler knew it also, but couldn’t pin it down. When someone decides not to trust the dog, the ramifications can, and often are, deadly.

In every conflict starting with World War II, what military dog teams have accomplished has been overshadowed by the sheer size of the war that encompassed them. It was true then and is the same today. In Korea, the impact of military dogs is miniscule, but not if you happen to be one of the soldiers that owes his life to one.

Robert Fickbohm was a handler with the 26th and worked with Hasso. In his book Cold Noses, Brave Hearts: Dogs and Men of the 26th Infantry Platoon Scout Dog, he says, “Between June of 1951 and the end of the war on July 27, 1953, they [the 26th] were never put in reserve. They gave support to every United States Division and went on patrols with many United Nation Units. The members were awarded a total of three Silver Stars, six bronze stars for Valor, and 35 Bronze Stars for meritorious service. Too many of them earned Purple Hearts.”

With the potential threat of chemical agents both handlers and dogs would be issued M6-12-8 gas masks. Photo: NARA

Did the handlers and scout dogs like Happy, Champ, York, Hasso, Arlo, and many others, have an impact on the war? I suppose it depends on your perspective. But the Chinese obviously did respect them. When front lines stagnated, the Chinese sometimes would set up loudspeakers and pierce the quiet night with propaganda announcements aimed at American troops. On one occasion, which is documented in military records, they bellowed, “Yankee – Take your dog and go home!”