WORLD WAR II

World War II

The Volunteer Effort

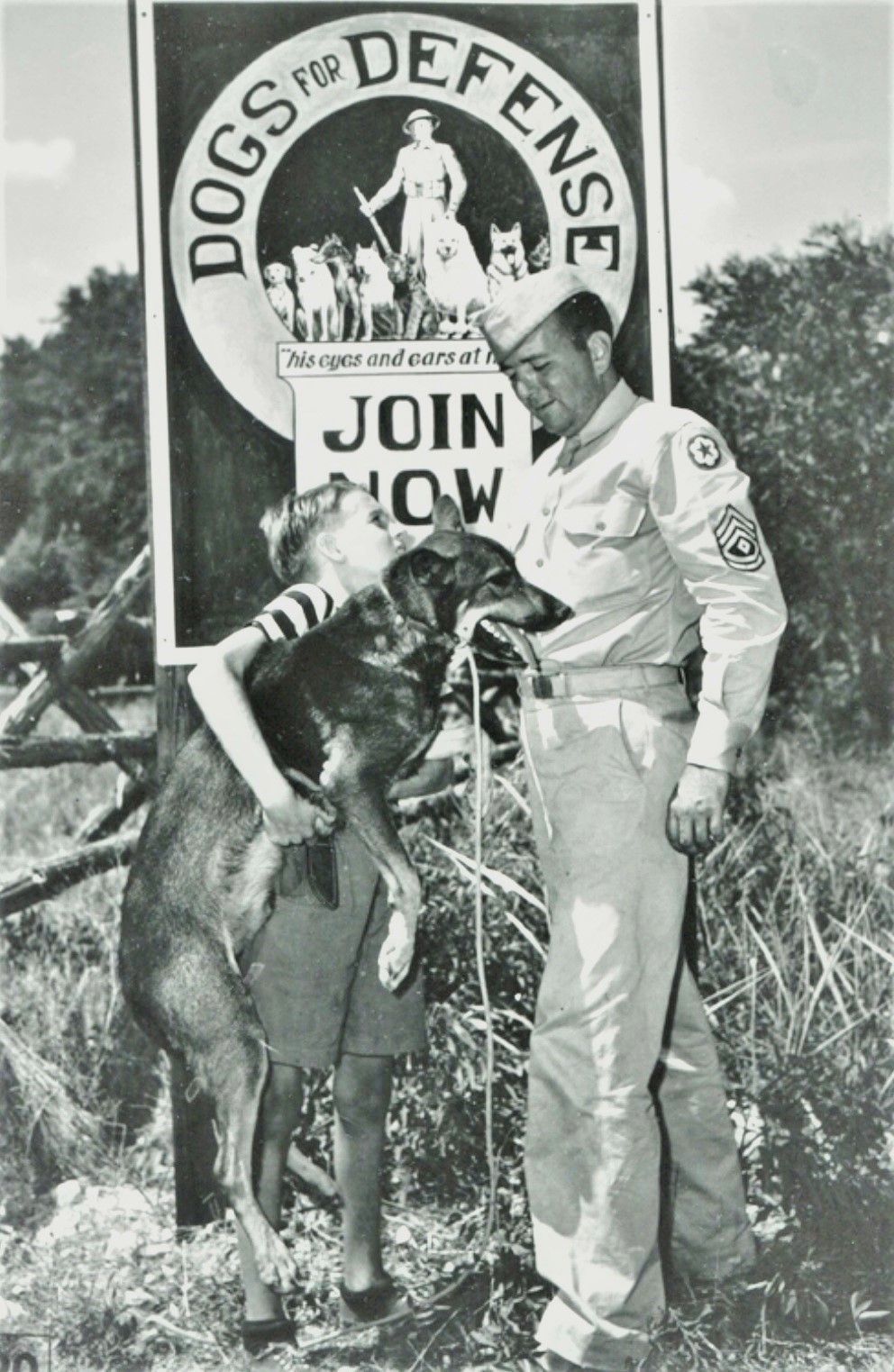

When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, the United States military possessed just a handful of sled dogs stationed in Alaska. There was no military working dog program. Alene Erlanger, a dog breeder and exhibitor residing in New York City, believed the military needed dogs to be part of the war effort. With help from the American Kennel Club and the Professional Handlers Association, an organization called Dogs for Defense (DFD) was launched in January 1942.

DFD was frustrated in trying to have a MWD program established. During March 1942 an experimental program was initiated to provide 200 sentry dogs for the Army. This early effort had mixed results as it involved both civilians and military personnel and a training syllabus had yet to be created.

Clyde Porter of Texas, donates his dog Junior to Dogs for Defense in this promotional photo. (NARA)

These first steps were undertaken by Lt. Col. Clifford C. Smith, chief of the Plant Protection branch, Quartermaster Corps, who was responsible for the security of not only military installations across the United States but also the factories that produce the materials needed for an all-out war effort. It was strongly urged that the use of sentry dogs would be advantageous against any sabotage operations.

A major change took place on July 16, 1942, when Secretary of War, Harold Stimpson, directed the quartermaster general to train dogs for other functions besides sentry duties. These abilities would include scout and patrol, messenger, and mine detection. Unofficially the Quartermaster Corps termed the war dog program, the “K-9 Corps.” The program would be expanded even further, providing dogs for both the Navy and Coast Guard. It should be noted that the Coast Guard maintained the largest contingent of war dogs, more that 1,800, for patrols along the east and west coastlines of the United States during World War II.

About 3,000 dogs were employed by the Coast Guard for shoreline patrol during the course of the war. (NARA)

During the war, five War Dog Reception and Training Centers were built at Front Royal, Virginia; Gulfport, Mississippi; Helena Montana; Fort Robinson, Nebraska and San Carlos, California. The Marines would conduct their own training at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Of special note is since all Army dog handlers were trained by the Quartermaster Corp, they were not eligible for the Combat Infantry Badge (CIB) even though many participated on combat patrol missions overseas.

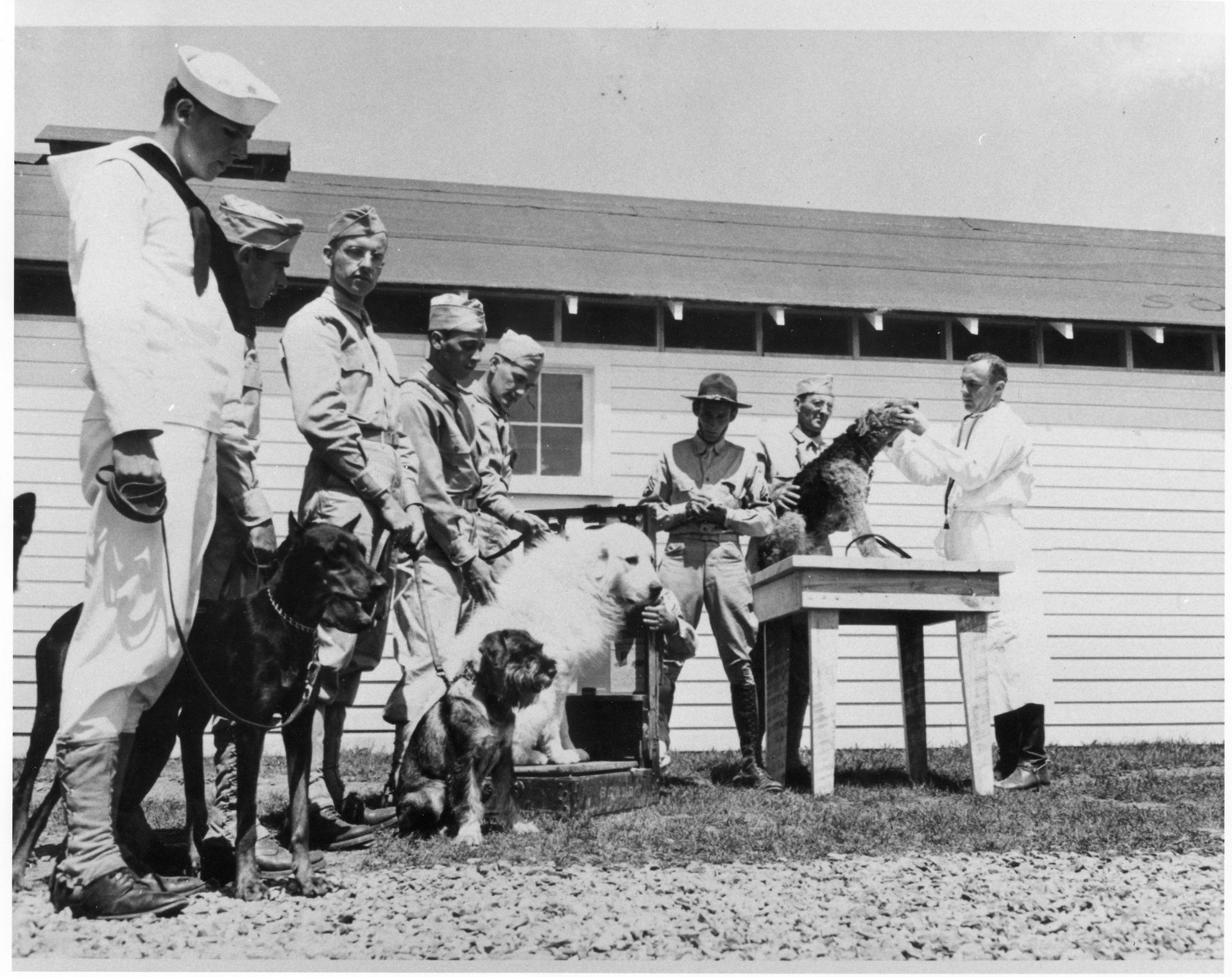

When first started, DFD accepted thirty-two breeds and crosses within the group. By 1944 this was whittled down to seven breeds; German shepherd, Doberman pinscher, Belgian sheepdog, Collie, Siberian husky, Malamute, and the Eskimo dog.

About 40,000 dogs were donated during a two year period. After a preliminary examination 18,000 were accepted at training and reception centers. From this group 8,000 failed exams based on temperament, improper size or health issues. This undertaking would not have been possible with Quartermaster Corps personnel only and was made manageable through the countless hours of time spent by DFD volunteers.

At the beginning of the war 32 breeds were accepted, all donated by civilians. (NARA)

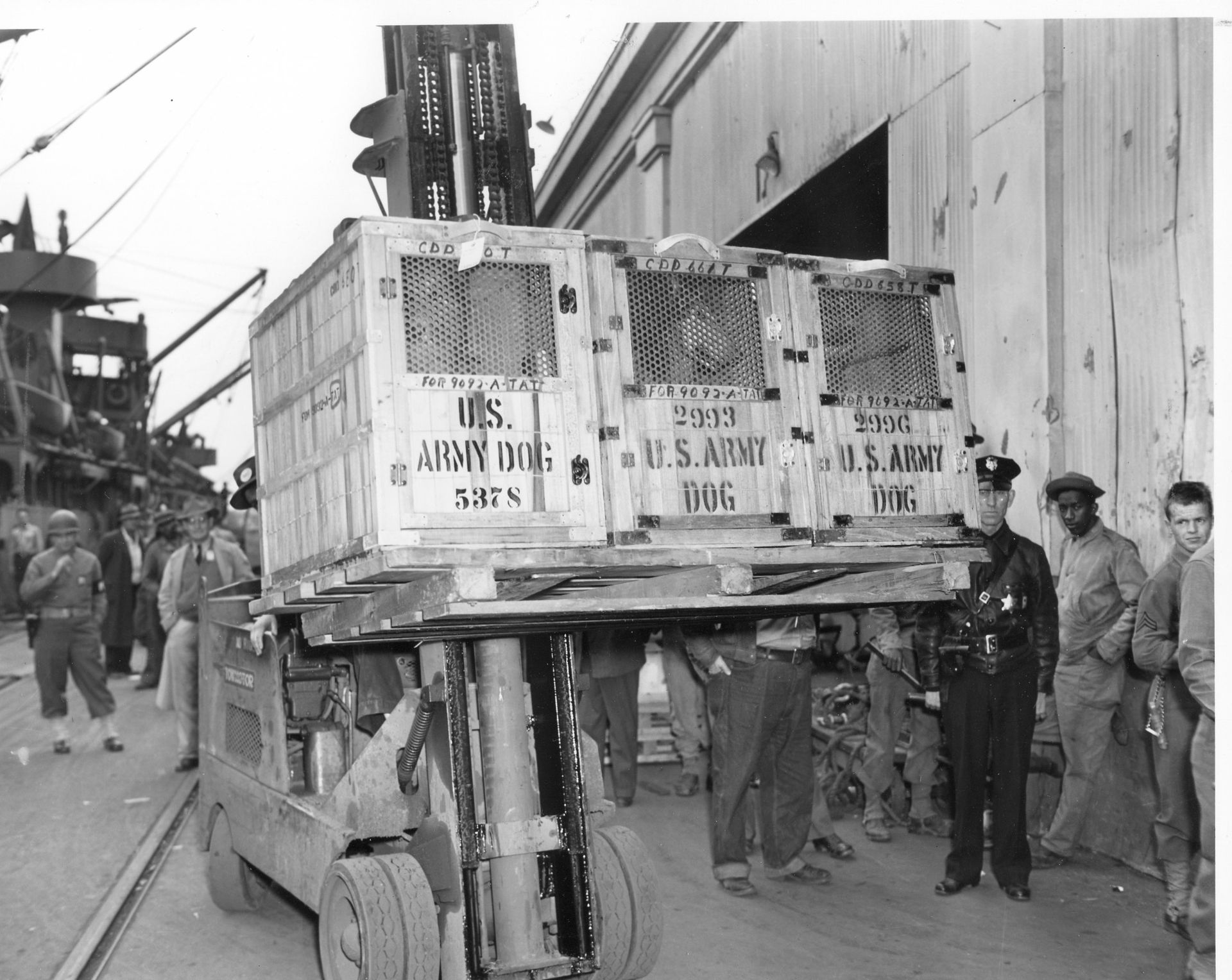

Dogs being delivered to a Liberty ship for overseas deployment.

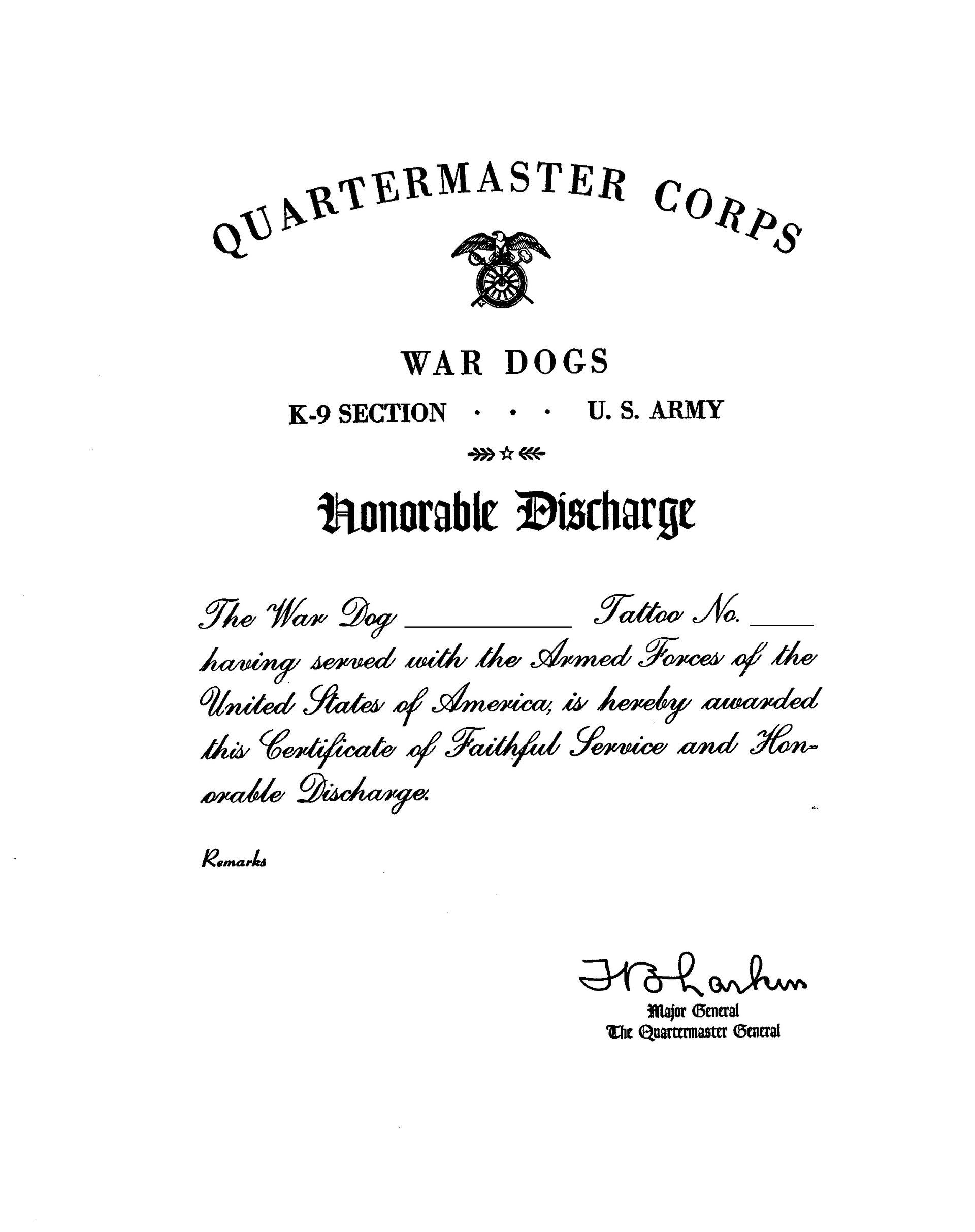

The dogs that were deemed acceptable were tattooed in the left ear with a serial number. This process was called the Preston brand system was first utilized with horses and mules. The system made it possible to tattoo 4,000 dogs with a single letter and a combination of numbers (although the Marines simply numbered their dogs). It is a practice stilled carried on today even though microchips are inserted in all military working dogs.

Lucy (N430) retired in 2011 and sports her distinctive tattoo and was also micro-chipped. (Lemish Collection)

The Coast Guard employed about 3,000 dogs for coastal patrol until it became evident by 1944 that a coastal invasion would never occur and it was highly unlikely a large numbers of infiltrators or saboteurs would come ashore. Tactical dogs were deployed in both Europe and the Pacific and also the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater of operations.

Marines train with their newly acquired war dogs at Camp Lejeune. (USMC)

Although the Doberman is closely associated with the Marines, German shepherds accounted for forty percent of the dogs employed. (USMC)

Many army officers questioned the usefulness of the K-9 Corps, believing that dogs maybe appropriate as sentries on the home front but not in front line combat situations. Fortunately success came early and helped bolster the canine program. And this could be attributed to Chips and a member of the first war dog detachment sent overseas.

Chips, a mixed-breed German shepherd, husky, and collie was donated to the army by Edward J, Wren of Pleasantville, New York. Chips was paired with handler Pvt. John P. Rowell and the pair arrived in French Morocco in October 1942, performing mostly sentry duty. In July 1943, they wound up in Sicily as part of an amphibious landing as part of Brig. Gen. George Patton's Seventh Army.

At about 0420, in the early predawn light, Rowell and Chips worked about 300 yards inland and came under machinegun fire from a camouflaged pillbox. Chips broke free, throttled up, and ran ahead. Moments later the firing stopped and an Italian soldier emerged from the pillbox with Chips attached to his arm. Three more soldiers immediately surrendered. Chips suffered a minor scalp wound and some powder burns.

Word quickly circulated within the division about the dog’s exploits and the press seized on the story of the “hero dog.” A month later Chips was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, and Purple Heart. Eventually all these awards were rescinded as they were intended for humans and not animals. On the home front, Dogs for Defense enjoyed the publicity coup, urging more Americans to donate their dogs for the war effort. Chips would also be included in two addresses to Congress.

Chips as he appeared in Italy. He was retrained and discharged from active service on December 10, 1945 and returned to his owners in Pleasantville, NY. (NARA)

Ready for Combat

All dog training in the United States military beginning in the war consisted of just basic obedience with no specific tactical requirements. The Quartermaster Corps had zero experience training scout and messenger dogs but were fortunate to get assistance from Captain John B. Garle director of the War Dog Training School in Great Britain in February 1943. Garle along with several handlers and dogs toured all the training facilities in the United States. This assistance would push the development of a practical training regimen for the K-9 Corps and establish the initial training manual.

This advancement in training would bear fruit with the invasion of the Japanese held island Bougainville in the Solomon Islands during November 1943. The First Marine War Dog Platoon, attached to the Second Marine Regiment (Provisional) came ashore one hour after the initial landing amidst Japanese mortar shells that still peppered the beachhead. Among them was Pfc. Robert Lansley and his Doberman Andy (71), Rarely done at that time, Lansley worked Andy off-leash and would get the dog’s attention with a clucking sound followed by a hand gesture. Considered an easy dog to read, the pair alerted to three separate enemy positions as they moved forward. The Japanese were addressed by the accompanying Marines with no losses among themselves.

Private First Class Robert Lansley and Andy, an off-leash Doberman. (NARA)

The first canine casualty of the campaign occurred on the third day. Caesar (05H), a German shepherd dual trained as a messenger and sentry, was handled by both Pfc. Rufus Mayo and Pfc. John Kleeman. On that morning Caesar jumped from a foxhole shared with Mayo and ran toward the unseen enemy. Mayo called the dog back and as he was returning an enemy sniper felled him with a bullet to the shoulder. During the firefight that ensued Caesar went missing but was later found with his second handler Kleeman.

Marines rigged a stretcher and took turns carrying the wounded dog to the regimental first aid station. The surgeon considered removing the bullet too risky as it was near the heart. Caesar returned to active duty about three weeks later with the extra weight of a bullet in his chest.

As with any new endeavor there were growing pains. Six dogs and all the females became overly gun shy and nervous, forcing them to retire from the front. Other dogs would pick up the slack like a pair of Dobermans named Jack and Otto. Jack alerted to a sniper in a tree and Otto scented a machine gun emplacement one hundred yards distant. Another Jack, a German shepherd messenger dog received two bullet wounds but still completed his mission.

The early success the military working dogs in the Pacific was not mirrored by their European counterparts. There were several reasons but two of primary importance; The terrain in Europe was much more open than that found on the islands in the Pacific theater. Another was that the olfactory abilities of dogs were not truly understood. Americans and Europeans based their diet primarily on wheat while the Japanese (and Asians in general) relied on rice as a primary ingredient. For dogs this meant a world of difference and why they were so effective for the American military in Vietnam.

On January 24, 1944, 108 dogs, 100 enlisted men, and two officers, boarded a Liberty ship bound for Kanchrapara, India, which is located near Calcutta. This group would be the K-9 component for the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations. Many dogs were retained at numerous facilities as sentries – not for enemy attacks but to counter the widespread pilferage that took place.

The scout dogs would prove successful like their Pacific counterparts but also suffered from the same maladies that plagued the dogs everywhere. Common parasites and skin diseases cropped up like dermatitis and eczema. Stomach distress was prevalent on a daily basis due to poor quality food and water. The handlers were not immune and subject to malaria, typhus, and dengue fever.

Since the detachment had split up among many assignments the dog teams were considered curiosities to the infantrymen and did not feel at home with anyone. As transients, they considered themselves as war orphans and took up the slogan, Nay Momma, Nay Poppa.”

Jesse Cowan and Kane on patrol in Burma. Kane belonged to Cowan's sister. Cowan and one other handler were the only men that enlisted together with their dogs during the war. (NARA)

Hits and Misses

Overall the military dog program was proving successful, yet some endeavors proved to be abject failures. In 1942 a Swiss national named Pandre convinced the Army that he could train a pack of dogs to attack the enemy in combat. He was awarded a contract and training would be conducted on Cat Island, eight miles south of Gulfport, Missouri. After viewing almost 400 dogs at various training facilities, he selected just twelve for the experiment. Things went south pretty quick with his arrival on the island in October. Complaining about the conditions there he went on to request horses, kennels, food rations and strange training equipment. He also requested twenty-four Japanese soldiers to be used as “live bait.”

The Army was not at all comfortable with this for obvious reasons but relented to the use of twelve “volunteers.” These men were secretly brought to the island. Overseeing the entire project was Lt. Col. A.R. Nichols from the Army Ground Forces (AGF). Nichols soon realized Pandre was not only eccentric and a huckster, he was probably a little nuts. Nichols despised the man on how he treated and trained the dogs provided to him. Nichols asked Master Sergeant John Pierce to come and review the progress.

Pierce was an Army dog trainer in California and came to the island with his own German shepherd, a grandson of the famous Rin Tin Tin. Pierce concurred with Nichols the whole thing was a farce and a waste of time of money. Pierce proved you can train one dog to attack but not a whole pack. Nonetheless training was allowed to continue.

A demonstration was made on January 12, 1943 with a Colonel Ridgely Gaither in attendance. Gaither later remarked the event as “...somewhat of a vaudeville animal act.” Pandre was immediately let go but complained that the entire program was sabotaged and he would tell the War Department and Americans just that. The Army requested the FBI keep an “eye” on the man going forward.

Another program soon began on the island the involved teaming messenger dogs with carrier pigeons from a detachment of the 828th Signal Pigeon Replacement Company. This program turned out to be productive and provided another form of communication for combat troops.

The training had dogs deliver pigeons to a bivouac area four miles away that could not be covered by jeep or on foot. Within a couple of months training was terminated – not because of the heat but the continuous onslaught of mosquitoes. Army personnel, dogs, and pigeons were under constant attack. The mosquitoes won and everyone gladly left the inhospitable island behind.

Another experimental failure would be the “M-dogs” or mine detecting dog program. In North Africa in the spring of 1943, the Germans were retreating and periodically planted nonmetallic mines behind. Electronic metal detectors were ineffective and a suitable countermeasure needed to be found.

The QMC decided that since dogs can find buried bones it would be natural for them to locate buried ordnance. Two methods were developed. The first was to reward the dog if they located a mine or trip wire. The second was the repulsion method whereas a dog would get an electric shock if the mine or trip wire was touched. This simple technique taught the dog that anything buried in the ground could hurt him. It was a faulty premise from the start.

As noted, humans were only beginning to learn the olfactory abilities of dogs. Thus dogs were trained to where humans may have disturbed the earth and not the scent that emanated from the mine itself. At a test exercise given at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, dogs missed 20 percent of the buried mines and numerous marks were placed where no mines existed at all. Few at the time worried about those not discovered and the consequence of the dog and handler who stepped on one. Based on just one demonstration, 100 dogs and handlers were trained and sent overseas to Ital in May 1944.

Future training was dismal with dogs only able to locate 30 percent of the mines planted. Add in the fact that the dogs were not subject to artillery, gunfire, dead bodies, and the debris left on the battlefield. Field commanders were also expecting 100% accuracy.

The experiment quickly fell apart but was doomed from the start, not because of the handlers and dogs but the lack of knowledge and the training regimen involved. Decades later, the M-dog program would be resurrected and provide outstanding service. The difference would be time, money, and the acquired knowledge of what dogs were capable of.

But the success of the Army and Marine scout dogs in the Pacific was indisputable as the Americans advance towards Japan. The first action for scout and messenger dogs on Guadalcanal took place on July 16, 1944. During action along the Numa-Numa trail, Army Private Simpson and his dog volunteered to lead a patrol to an important position. Simpson got the patrol to the desired spot with no casualties and was recommended for a Bronze Star. Word got out and the request for dogs from the 164th and 182nd Infantry came more frequently. Several dogs were killed in action during this same time period although they had been working perfectly and alerted to numerous enemy positions.

The 26th QMC War Dog Platoon arrived in New Guineas during this same period and proved to be a tactical advantage in the dense jungle. The scope of the patrols ranged from small five-man reconnaissance units to rifle companies with over two hundred men. The CO of the 155th Infantry Regiment stated in one report, “Of equal importance is the ability of the dog to pick up enemy bivouacs, positions, patrols, troop reconnaissance, etc., long before our patrols reaches them. This advance warning has frequently enabled our troops to achieve surprise and inflict heavy casualties on the Japs.”

Nompa, a scout dog, checks a hidden cave on a coral cliff on Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. (NARA)

The 26th Quartermaster War Dog Platoon starts out on a patrol on Aitape, New Guinea. (NARA)

On July 21, 1944 two Marine war dog platoons landed on Guam which was being held by about 19,000 Japanese soldiers. The Japanese realized the asset the war dogs provided the Marines and targeted them with rifle fire resulting in about ten dogs being killed. Although the island was declared liberated on August 10, the remaining Japanese still conducted guerrilla operations and the ensuing mop up actions resulted in fifteen dogs being killed. The Japanese was not the only enemy encountered as many dogs suffered from malnutrition, tropical diseases, and filariasis.

Once the island was secured a large airbase was built to support the B-29 Superfortress attacks against Japan. At least 350 dogs spent some time on the island and became arrival and deployment location for Marine war dogs during the balance of the war. It was also determined at this time that messenger dogs were no longer required as communications improved. They were retained for night outpost duties and some were retrained for scouting. It was also determined to no longer accept Dobermans as replacements as many were temperamental, excitable, and nervous compared to German shepherds which became the breed of choice whether they were male or female.

The Marines honored their war dog dead by establishing the cemetery on Guam. In 1994 the entire cemetery was moved and rededicated through the efforts of William Putney, D.V.M who served on Guam during the war. (NARA)

After Guam, Marine war dog platoons participated in other battles in the Mariana Islands, the Palau Island group became the last steppingstone for the invasion of the Philippines. One island, Pelieu, just six miles long and two miles wide, held ten thousand Japanese soldiers in more than five hundred caves. Several dogs suffered from what was at the time called “shell shock” but better known today as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The Philippine Campaign that launched in January 1945, included six QMC War Dog Platoons. They worked continuously until April. In a report to the commanding general of the Sixth Army, the 26th's CO, 1st Lt. James S. Head, reported: “The dogs of this organization are directly responsible for the saving of considerable lives as well as the destruction of the enemy. Had more dogs been available for deployment, the number of lives saved and the number of enemy destroyed would have been proportionately larger. The 6th, 25th, and 21st Infantry Divisions have each requested permanent assignment of a very much greater complement of War Dogs.”

On January 2, 1945 a 5th Marine division dog handler, a Navy chief hospital corpsman, board a transport for Okinawa. The war dog is trained to carry blood plasma that can treat eight soldiers. (USMC)

For the invasion of Iwo Jima, on February 19, 1945, the Marines deployed two war dog platoons. On the first night Pvt. James E. Wallace was killed by mortar fire and his dog Fritz (255) was wounded. The following night Carl (441), a Doberman pinscher, alerted his handler Pvt. Raymond N. Moquin, a full thirty minutes before an enemy attack. Fully prepared the Marines wiped out the attackers. The following day King (456) was wounded by shrapnel and Duke (330) was killed by a sniper. Dogs alerted numerous times to infiltrators the following nights as Marines attempted move inland.

Conditions on Iwo did not warrant the extensive use of dogs-owing to the extensive artillery and small-arms fire across the wide open terrain. Because of the noise and confusion, dogs on patrol alerted not only to the enemy but also to the dead Japanese that littered the landscape. The tiny volcanic island would not be secured until March 26, 1945 at a staggering cost of 6,800 marines killed and another 18,000 wounded.

The battle for Okinawa (code name Operation Iceberg) began on March 26, 1945. Okinawa is the largest island in the Ryukyu chain and covered 794 square miles or little larger than half of Rhode Island. Similar in terrain to Iwo Jima, Army and Marine platoon leaders would soon find out that their men and dogs would play limited roles in this engagement and often misdirected by the upper echelon.

Arriving two weeks after the initial assault,1st Lt. Wiley S. Isom. QMC 45th War Dog Platoon was ordered to provide fourteen dogs to assault a strongly defended Japanese position. As Isom later stated, “...upon entering enemy territory the Japs opended [sic] with everything they had, including small arms, machine guns, mortar and artillery. There was so much confusion, so many people moving around, that our dogs were of no use whatsoever. Immediately our dogs were ordered to report to the rear.”

Marine Pfc. Hallet McCoy and his dog, both veterans of Peleliu, take a break on Okinawa.

Several other attempts were made to field scout dogs but yielded no results due to heavy artillery fire. Eventually it was time for mop-up operations to find the enemy hidden in scattered caves. Here, without the noise and confusion, the dogs checked the many caves and bunkers. But this work was also foreign to the dogs, and the smart ones refused to enter any dark space but would often alert at the entrance to the presence of enemy soldiers within.

The Army and Marine war dogs had done remarkably well throughout the war, considering that just about everything was a new learning experience. Scout dogs could not be used indiscriminately, and most of the negative results from Europe and the Pacific stem from this practice. When the need was specific and within the capabilities of the dogs, there was no question of their effectiveness. This is supported by the fact that the QMC had plans to establish sixty-five scout dogs platoons for the possible invasion of the Japanese homeland. The close of the war meant no more dog teams would be necessary, and the Army and Marine's attention was diverted to what needed to be done with its dogs.

Return of the Canine Veterans

A more ambitious plan than the recruitment of thousands of war dogs would be the decision to return them to civilian life. The return of canines involved the Quartermaster Corps, Dogs for Defense, and army veterinarians. Although the DFD offered to place all surplus dogs, as government property they needed to be sold unless being returned to their original owners. Depending on the distance the dogs were shipped, the price varied from fourteen to twenty-four dollars. Such a bargain! In an effort to keep costs down, everyone was expected to return the shipping crate and feed pan at their own expense.

Veterinarians needed to ensure that dogs returning to the United States did not carry any diseases that could be spread among the general dog population. Dogs determined to have leptospirosis or scrub typhus were destroyed locally. All dogs returning also needed to be vaccinated for rabies.

These dogs were well along in their retraining and would soon be discharged and returned to civilians. The army and Marines made an extra effort at the end of the war to return as many dogs as possible to civilian life.

Besides being physically healthy, all dogs needed to be retrained so they would have the appropriate temperament to re-enter civilian life. This process alone took about the same amount of time as their training did when they entered military service. Those that could not make the suitable behavioral change were either retained by the military or destroyed. The Marines mirrored this same obligation and returned 491 dogs to the United States and less than 30 needed to be euthanized for medical or behavioral issues.

One problem the military anticipated was a shortage of homes for the former war dogs. Actually the opposite came true, as the DFD received over fifteen thousand applications for the K-9 veterans-many more than the number of dogs available. This continued for several years after the war. World War II marked not only the beginning of a military working program, but the end of an era, when civilians were truly involved.

The army recognized the war dogs by issuing a discharge certificate upon their return to civilian life. This practice was discontinued shortly after the war when Dogs for Defense disbanded and the government prohibited the return of military dogs to civilians. (Lemish Collection)